Rejection

Rejection of the transplanted kidney happens because the immune system recognises it as ‘foreign’ tissue, and tries to reject or destroy it. To reduce this risk and increase the chances of a successful transplant, your child’s transplant team will try to find a close ‘match’ between your child and a donor.

Your child will need some tests to find out information about certain ‘markers’ on his or her cells. These are added to a large database (on a computer), held centrally by the National Health Service Blood and Transplant. This helps to find a suitable donor – someone whose markers are closely matched with your child’s.

Matching donors and recipients

Children are likely to need more than one transplant in their lifetime, and the better matched the first transplant, the easier it will be to match a second transplant. It is important to have as good a match as possible. Matching is based on several things. The two main concerns are: blood group and human leukocyte antigens (HLAs).

Blood groups

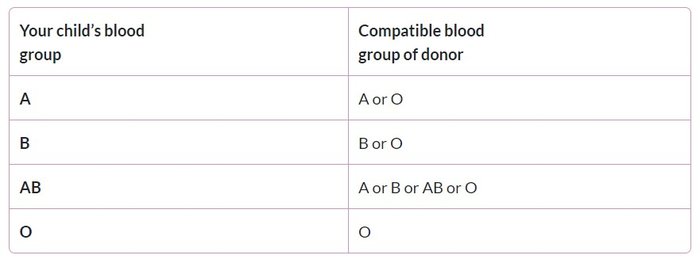

Our red blood cells, one type of living cell in the body, belong to a blood group. This is based on whether or not we have certain substances on our red blood cells in the blood. These are: A, B, AB and O. It is important that your child’s blood group is compatible (can match) with the donor’s blood group.

The following table shows compatible blood groups.

Tissue type – HLAs

We each have a tissue-type. This is based on ‘markers’ or proteins that are found on the surface of all cells in the body. These ‘markers’ are determined by our genes, and inherited from our mother and father.

Some of these protein ‘markers’ are human leukocyte antigens (HLAs). These proteins are part of the immune system, and help the body to tell the difference between our own tissues and foreign substances.

Our own combination of antigens is on cells throughout our body. Half of the antigens come from our mother, and half from our father. This means that our tissue-types are more likely to be similar within a family.

When a donor and a recipient do not have the same antigens, the recipient’s immune system recognises a transplanted kidney as foreign, and so may try to reject it. The closer the match, the lower the risk of rejection.

HLAs and mismatches

There are many possible combinations of antigens, so it is difficult to find a perfect match. However, your child’s transplant team will check the tissue-type of your child with that of a potential donor for a match that is close enough.

Only 3 pairs of antigens are used when matching donors and recipients. These are labelled with the letters: A, B and DR. We understand that our immune system reacts most strongly to DR. For this reason, the transplant team tries very hard to find a complete match for DR antigens.

More about matchability scores in Kidney transplant - deceased donors

Although it may seem confusing, when talking about the specific antigens, transplant teams talk about mismatches rather than matches. This is because it is mismatches that allow the immune system to recognise the kidney is from another person, leading to rejection.

For children having a deceased donor transplant, it is especially important to have a close match.

- A level 1 match (previously known as a full-house match) means there are no mismatches between the A, B or DR of the donor and recipient. This is the closest match, but is very difficult to find. It only happens in about one in ten kidney transplants in children.

- A level 2 match (previously known as a favourable match) is a less close match, but still a good match for a deceased donor transplant. This means there are no mismatches against DR and not more than one mismatch each between A and/or B. Between 2003 and 2012, half of the children having kidney transplants in the UK had a level 2 matched kidney.

- For children having a living donor transplant, it is acceptable to have a less favourable match.

In recent years, just over eight out of 10 children receiving deceased donor transplants have received either a level 1 or level 2 match. The others have less wellmatched transplants. This is because their tissue type was uncommon and/or they had to wait a long time for a suitable donor.

Antibodies

Antibodies are part of the immune system. They are made especially to fight specific foreign substances, such as germs, that enter the body. In organ transplantation, and after blood transfusion (receiving blood from a donor), the recipient’s body makes antibodies against the mismatched antigens on the donor’s organ or blood.

These antibodies may last for life and may prevent a repeat transplant with the same mismatches.